|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note

to readers: Portions of the following notes were originally written in outline

format. These portions have been editorially revised into sentences when

needed. The illustrations are close approximations of those made by Mr.

D’Arista. This material is not complete, with some small (and possibly large)

portions of lectures and some of the class assignments missing from the

original student notes. Notes copyrighted 1981/2004 by Judith Laue. This

material is freely available for nonprofit use. Please send email to

[email protected] to report typographical or other errors.

Student

Notes from “Special Studies in Painting: Composition”

A Studio/Lecture Course Taught by Robert D’Arista

Spring 1981, The American University

Lecture

Lecture

The root-2 rectangle (start with a square, draw the diagonal, then

drop the diagonal to the baseline) gives greater strength and force to the

internal structure of the painting. It creates and aligns forces within the

painting. Angled shape restriction might give more power and assertions of

forces. The right angle, L: vertical against horizontal, gives optimal

assertion of forces.

Consider

the possibility of regulating and even measuring this opposition. You relate

angles the way you would sizes, for example; here the direction is halved.

Simple

angled relationship.

Simple

angled relationship.

Bisecting still gives systematic relationship

between angles.

Bisecting still gives systematic relationship

between angles.

Seurat used a simple compass-like machine.

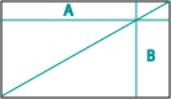

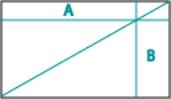

Inner square: Short length

(A) along the long length (D) of the rectangle forms each individual

rectangle’s inner square. Be very aware of the anatomy of the rectangle, but

don’t plan it out like a surveyor. Develop the painting. Have some shapes point

to the points of relationship on the horizontal and vertical framework.

The head is a series of thrusts within the canvas; not a circle.

Delacroix – very systematic. Fold a piece of paper and find the systematic

relationships upon the unfolding.

Begin the painting with a sketch, giving cognizance of the

rectangle relationships. Pathways can unite the canvas when objects are

scattered. Pathways direct the eye to the four corners and to where you want

the eye to go. Above and beyond anything else, make sure you can do that!

Whither the edge (of the line) goes, the eye goes.

There are certain priorities: Getting the eye around the

rectangle. Jumps: in music, there must not be unrelated jumps; rather, there

must be a subsequential movement. The lattice, rectangular relationships,

functions to make paths for the eye. This de Kooning figure is pinned to a

latticework of roads.

Portrait

Principles: Let lines go through the head respective of

the dimensions of the rectangle. This puts a series of tensions through it that

stops the endless circling that can happen with the head. Do this even with grapes.

Pythagoras

= Root-2 Rectangle

= Root-2 Rectangle

A

= Long side of original rectangle squared

B=

Short side of original rectangle squared

A

+ B = C

A2

+ B2 = C2

The

square of the hypotenuse of an angle equals the sum of the square of the other

two sides. But this isn’t mathematics. It is really primitive thinking. It is

savage.

A=B

A=B

We

are intrigued by systematic relationships. Claude Levi-Strauss The Savage Mind. This is the very beginning of relationships. The primitive

mind is the human mind.

Learn this elementary, childish trick of

expanding the rectangle. This keeps the relationship constant when enlarging or

decreasing the picture. This is why one must sketch first.

Learn this elementary, childish trick of

expanding the rectangle. This keeps the relationship constant when enlarging or

decreasing the picture. This is why one must sketch first.

In

a square there is no inner square. I never work with a square canvas.

= Distribution of the rectangle.

= Distribution of the rectangle.

A

and B are equal, but no one would ever guess it. This makes the mind jump –

intriguing.

The

head is not static, but part of the whole thing. The head should not be a

static round thing that your eye can’t get out of. Instead of softening lines,

bring dynamic lines through to create dynamic tensions.

It’s

not indifference – we see the tensions, but we don’t exploit what we see. The

diagrams do not restrict expression. Even though poetry has rhymes, it does not

hinder what is being said, but gives speech the beauty of metered sounds.

Passion. The constrictions on language enhance the expression.

Geometrics

![]()

1.618 harmonic ratios.

The

Golden Section. Fibonacci series – pinecones,

rabbits. Rabbits: two rabbits are in a

cage. With a little luck, another will appear. The little rabbit will grow to

be quite incestuous, and now we have 5 rabbits. Soon we’ll have 8, 13. This is

the way of the world, you might as well understand it. It is the same with

pinecones. The product of the sum of the two previous sums. The dynamic

mechanism is always the same.

All

are different, but all are the same. Sameness can be seen as being

multifaceted.

All

are different, but all are the same. Sameness can be seen as being

multifaceted.

Philip

Guston said, “A painting is a thing.” It has an anatomy.

A

and B have the same weight, with different configurations.

The

dotted diagonal is at a right angle to A, then bring down line C.

Identical

proportions to a series of identical relationships.

Compelling.

The simplest possible relationships.

A and B have equal proportions.

Musical

scale is based on the same system of relationships.

Implications

of using the above diagram: Big jumps

and tiny jumps become possible, because you can relate them. Architectural

jumps – you can move up and down through the scale in an exciting way, without

losing the sense of relationship. Illiterate modern painters talk about shape

relationship. The painting itself is the most important shape.

Golden Section

1.6 Bisect a box, make a diagonal.

Bring the diagonal down, and get the golden section. Then, find the inner

square bisecting line.

1.6

(golden mean?) x 4 (side of rectangle) = 6.4

Because

it is so simple, complexity is possible.

Lecture

Make

a square, take the diagonal down to a root 2. And another down to a root 3.

New

idea = The spiral. Being controlled by an increment of growth. The way things

grow. Geometric progression away from an axis. Snails.

Generate

forms on the spiral and small mirrored rectangles form.

If

the rectangle is too even, this won’t work.

If

you choose not to use formal composition, still understand what it is. You are

intuitively doing it anyway. Hemingway does not get lost in long descriptions

of armor, as does the Odyssey. But both

his epic and Homer’s are grounded in particulars – that is, warfare and fishing

– and both transcend those particulars to arrive at their subjects. The Old Man and the Sea is about

endurance. The Odyssey is about the

wrath of Achilles

In

review: the eye moves along paths. Angles generate relationships and compositions.

We have to make relationships that move through the entire length and width of

the whole painting.

Frontality

Diagrams

reflecting concern of opposition of forces (tensions). The purest form is the

vertical against the horizontal. Why is it that only the vertical and the

horizontal, as with Mondrian? Why not the diagonal? Because it is clear that

when painting is like this (see illustration), we assign greater stability to

the painting.

Diagrams

reflecting concern of opposition of forces (tensions). The purest form is the

vertical against the horizontal. Why is it that only the vertical and the

horizontal, as with Mondrian? Why not the diagonal? Because it is clear that

when painting is like this (see illustration), we assign greater stability to

the painting.

We

assign a certain stability to the horizon. Lay down a ground plane, a stable

earth that can support things.

The

early artist fights with perspective to lend a certain stability to the

painting. The grid gives this stability without distorting. So the artist feels

freer to come in at an angle, to have your cake and eat it too.

However,

at the same time, this horizontal may foil the sense of gravity. We play with

associations that we and the audience make. If associations are real and

universal, then we must take them into account. Blue: sky, space, foreverness.

Subtleties

taken into account can give a complicated series of stylized movements, each of

which can mean something (Seurat, Kandinsky). Instead of using obvious motions,

construct a series of subtle ones. At the heart of such a view, you get Kandinsky

saying, “This is energy” (head going up). Reduce and formalize the cues. The

diagram can work with this. Yin Yang, etc.

Diagrams

make a series of signs more easily understandable. You might think formalizing

constricts and inhibits, but it is the opposite. It makes the deviations from

the norm more understandable.

Likeness

or strong associations? When is it

necessary to give up likeness for association? This is the difference been

prose and poetry.

Frontality

of Painting: Frontality as opposed to

space. Frontality is defined as

something facing us, not any object facing us, but the thing being gotten

across. (D’Arista shows Cezanne’s “The Card Players”).

In

Baroque painting, the principal plane does not face the viewer; it is angled to

create space (diagonally sweeping away from view), causing it to be profoundly

deep and unclassical.

High

Renaissance figures are frontal. (D’Arista draws a simple frontal view of a

face - ‘Mommy’) It takes the kid 15

years to do a three-quarter view. Phylogenetic

– a term. We have each evolved from the amoeba, through our own development,

telescoping the history of life.

Morandi

confronts us. Which is more sophisticated? Morandi or Caravaggio? Morandi is,

although the chemistry student would say ‘Caravaggio’. By sophisticated we mean…?

We

are concerned with sharpening artistic skill and perception, but what are we

doing as artists? If poetry becomes too discursive and intellectualized, a lot

becomes lost in terms of the crude primitive forces that drive us to poetry. A

good deal is lost as art becomes too elaborate.

There

is a kind of sophisticated person who sees true sophistication in terms of

neoprimitivism. The principle of frontality is an assertion of reverting to

basic principles of seeing. If then you see Morandi, you see simple force, with

objects being presented in a simple way. You see perhaps – you’ve been looking

at him (Morandi paintings) for too long, and you forget their urge to get at

something more elemental.

If

you are a born compromiser, you’d say, “Well, need there be this mutually

exclusive series of principles?” The right-angled diagrams retrieve the

elemental.

To

the extent to which an artist can be simple and primal is very desirable. Some

things cannot be said simply, as this lecture, but it is up to me to clarify

with something simple.

There

is much to be learned by comparing Morandi, Caravaggio, and Mondrian. This

leads us to further understand the grid diagram, because it is a series of

parallel diagrams – that it can compensate for serious problems. What I hope

you will get out of this lecture is some awareness of the forces you are

unleashing upon the canvas.

Space

There

arises the issue of control and composition of space. Space: The 3-dimensional

cues of the painting. With our background, the more space, the better. We spend

a lot of time trying to make painting work spatially. But many see space as the

archenemy of painting. Contemporary painters want to destroy space. The

flatter, the better. Traditional view: paintings have integrity of the picture

plane (Duncan Phillips view).

What

is the picture plane? It is the rectangle you paint on. The plane through which

the light passes finally in the articulation of the painting.

To

Kandinsky and Mondrian space is original sin. To the Impressionists, painting

with a hole in space is the only problem they are concerned with. If there is a

hole in a painting, it means it is a deep pit compared to the rest of the

painting. Now then, if the hole is a problem, we can say that as objects fall

back, the painting weakens.

The

more you gray, the further back you get, with the idea that you get space. But,

it might fall back too far, plunge down, and make a weak hole. To many artists,

any plunge in space weakens the painting.

To

the extent that you are aware of the picture plane, the painting may be more

spatial. You’re at the beach – mid afternoon, the sun is hazy. People are

diving off the shore float, with sun haze; the float looks 15 to 20 yards from

shore. The next day, it is clear. The float looks 10 yards from shore.

In

a medieval cathedral a cluttered up hall looms enormous. The next hall is empty

and appears smaller, because there is nothing to measure space against. If you

are to measure space securely, measure it against something.

The

grid can do this. There is a scale in terms of space. The grid may hold the

picture plane and painting becomes a bas-relief in which there are cuts. Make

space measurable and understandable in terms of something else.

Bob

Gates [a painter friend and colleague] said, “You can go into space as deeply

as you wish, as long as you come out again.”

If

there are measurable relationships throughout the painting, you’ll be secure in

the painting. Space must be controlled. It can be a culprit. The presence of the

grid can hold the surface.

Classical

space: three planes as in bas-relief. Construct the Greek frieze – paintings

have three planes. Raphael – figures are in one plane; background, one plane;

foreground, one plane. Against the plane of figures – you cut into the matrix

….

Why

do we destroy the frieze Mr. Boul [a painter friend and colleague] sets up?

Object cognizance. The introductory plane, frieze plane, and background plane

create classical space. This organizes space, simplifies it. Minimizing space:

Why do this? Mondrian, cubists, close the window and restrict the space.

Space

may be bad for a painting, and it may be bad for you. Kandinsky wrote On the Spiritual in Art. You have wanted

to be spiritual in art. But you have been inhibited by Mr. Boul saying, “paint

that damn pot and rug.” The best way to get spiritual (non-material) is to get

rid of the context in which things happen, which is space.

Rembrandt

does not paint space like Vermeer. The absence of palpable material in

Rembrandt greatly enhances spiritual quality and transcendental quality. The

absence of rooms and articulated space enhances spiritual quality. I am of this

opinion that too much space can be real trouble. Space is the archenemy of

elevated energy. In Mondrian’s essay on neoplasticism, “We must transcend

object and space,” Shiites and Manicheans– opposers of the material.

Lecture

We

have mentioned two devices:

1.

The reduction of planes by finding the silhouette.

Remedy

of holes – color and light, activity In discussing space and its composition, I

have given you a simple device to help you understand Morandi, etc. The frieze

and classical space – three planes. Why three? There is no magic in this

number. Something is far, close, or middle ground. If there is a rupture in the

movement across the picture plane, there may be a hole. Also, lines move the

eye through the picture plane. The line (firm silhouette) holds the objects on

the plane. But there is more than one cue to hold space. This line will

function even to counteract deep space such as linear perspective

(convergence). Raphael uses linear perspective like gangbusters, but also the

frieze. No randomly dispersed figures.

II.

Space is the archenemy of transcendental painting.

Transcendental

painting: Idealism – (Plato) true essence of an object is not the object but

the idea of it. Man as a concept, not a person. We are moving towards pure idea

to be perfected. Symposium on the nature of love and the nature of the sublime.

Physical love is the lowest level of love. The beauty of a young lady in her

prime is of the lowest level. We have the same problem with a gorgeous, vulgar

sunset.

As

you move towards an idealized notion in art, it is consonant with true

morality. True morality – the movement toward pure ideology. As you move from the things of this world,

you move toward the spiritual (Neo-Platonism). To the Transcendentalists –

Raphael, Michelangelo - to them, painting is the ideal way to express man’s

movement toward perfection of idea. Raphael painted an idealized figure because

of the exact mathematical proportion.

Mondrian

was a theosophist. Caravaggio – everyday people … Raphael did transcendental

paintings of the nonexistent, making them transcendentally real. Manichaeism –

in this country found in the Shakers. No children. Sex generates life, and life

is evil. The Nabis.

The

West has always been rational. As you age, you move towards the more sublime

elevation of pleasure. The movement towards morality. Morality and

enlightenment and sublimation are one and the same. And we understand when we

are ready. True knowledge is secret (kabalistic). Mondrian sees the figurative

as evil. Western art is dualistic. You can’t make sense out of the

Judeo-Christian faith. The spiritual is constructed out of the grist of

experience. Progressive sublimation occurs in Rembrandt.

You

should not wonder at this conversation. There has been an enormous triumph of

transcendental art in the country in the past 25 years (abstract art). My deep

western bias says transcendentalism must come of experience. Whitehead, In The Function of Reason (morphology)

wrote that higher thought is associated with more complex forms. The amoeba – a

blob – eats and has sex. It thinks in that it reacts to sensation. A daisy –

symmetrical. The Fly Trap is a highly evolved plant. As you move towards the

more complex organisms, you have more complex thought. You move through the

physical to the transcendental.

In

the meticulous articulating of the model you may not achieve art. In fact, the

particularity seen in Rockwell may militate against acceptance of it as sublime

art. The pure neoplatonic idealism (Carracci

bros) - you might find serious problems. Rembrandt’s real achievement may exist

in movement through the vulgar and trite to transcendental experience, an

equation that suits the west to a tee.

The

photograph won’t do it. Photography seemingly obviated the need for figurative

art. Yet I would suggest nothing of the sort. You yourself have real

reservations about the movement toward the literal. Ponder what they may be.

There is a remote possibility that you like that painting (a student’s) because

there is not as much space as there could be.

Approach

each painting or quick sketch as though it were to be exhibited, a work of art.

It is the only way to make progress, and otherwise, you train yourself to be a

sloppy artist and poor habits ensue. It

is well understood by pedagogues that on the piccolo you must begin by playing

so slowly that you make no errors and gradually build up your speed.

Lecture

The

grid is a 2-dimensional device and thus implies the picture plane. It reasserts

the rectangle. This would presume that space is not evil, but must be

compensated for. The simplest way that space is introduced into a painting is

the juxtaposition of contours. Even when objects are perceived as being behind

each other, they are still on the same plane,

when in the frieze.

An

object or figure falls out of a painting. Why? Volume is a very persuasive

device to imply space. We do make space with volume. With the head, you can

have the 3 space planes by using volume.

Aerial

perspective: as things go back, edges are less defined and grayer. Softer

edges. With linear perspective things become smaller. Things get cooler, less

bright, less contrast

Leonardo:

The figure is first a dot, and then a lozenge as it comes closer. Soon it has

color and you see his face. When you see the whites of his eyes, you shoot.

This is true for gun fighters.

It

follows, that when you paint a landscape, black and white colors are not

perceived as strong when they are in the distance. All colors and value gray as

you move back in space and become somewhat cooler. You can compensate going

back too far by sharpening. However, you can put blue in the foreground by

graying the background, etc. Our artist, blundering through life, finally comes

across this solution after some 8 or 10 years of hit or miss.

Jack

Boul [a painter friend and colleague] as a young lad was out painting in the

woods. His instructor told him to stay and something would happen. Sure enough,

a cow comes by, and Jack puts him in the painting. But the cow doesn’t work in

the painting. It is too sharp. Finally, he got tired of painting it and scraped

it off, only to find that now it worked as a blurred shape.

But

then, a more modern day painter comes by and says, “you have disturbed the

picture plane integrity, so put red in the background.”

A

contradiction? It is only in the landscape that the elements of space are

addressed vehemently. How is this done in the figure painting? Exaggerate it.

If a figure has a great amount of detail next to a deep plunge of space, then

it must be modified. Put something strong into the space.

Composing

values: Cennini: Make flesh tone, have three values: light, medium, and dark.

Corot used 11 values. Very subtle painting.

Sometimes

a partial solution is more dangerous than no solution. Like introducing

plumbing into society – causes pollution, etc. Progress.

One

incidence next to another. Moving frieze-like across the painting begins to

occur. Our concept of painting has changed. During Raphael’s time, the figure

is integrated into surroundings by the grid.

A

painter who paints from imagination will make compensatory movements of color

light through the painting. You must understand the continuity of things in

space.

One

doesn’t just see only the nose, so one shouldn’t just paint only it. Otherwise,

there are holes. The activity of detail can hold the foreground. Also, detail

in deep space can hold the background, as in Paul Gauguin. Sometimes it is not

just the color, it is the activity.

Class

exercise: Start a painting incorporating several of these ideas. Put straight

lines around shapes of light reducing objects to about five planes. Make it

three values, 3 planes. Introduce three colors:

Pure

cadmium yellow: value 1 = high

Cerulean blue: value 2 = middle

Deep

red: value 3 = dark

Make

sure there are as many planes in the background as in the middle ground. The

painting will have equal intensity throughout. Then on Thursday, complete the

painting with more natural values. Deepen it or flatten it out.

We

put the correct colors over the red, yellow, and blue painting. We worked the

frieze across with three planes. Use of straight lines. The grid device relates

the movements through. There can be complex movements, but they’re held by the

grid and the planes within.

One

ray permits us to see the light. The further the light bulbs are from the eye,

the lower the ray is that hits the eye, approaching the horizon.

We

speak of the eye level as the horizon. As the eye goes up, the horizon level

goes up. This is linear perspective. The vanishing point is always on the

horizon. Eye level is the horizontal trace.

Every

point of a still life reflects a beam of light on the eye. The surface of the

painting is the capture of each of these points. There can be more than one

vanishing point, but they’ll all be on the same vanishing trace.

Light and its

use in the painting

This

is not a complicated matter. Simply, one understands the light as establishing

a hierarchical priority to the objects. It gives the sequence by which you will

see things.

As

you develop the painting, the eye is attracted to where the marks are not, to

where the light is. The marks all compete for attention, but the light captures

it. The most unpainted parts are the lights.

In

a drawing, you tend to look where the mark is; but in a painting, where the

light is. This is a very primitive and dynamic and important thing. Control of

the light is very important. Light ceases to be merely an accident and becomes

a contrivance for orchestrating the visual experience.

The

eye can’t escape the dynamics of the painting – the light. Now, you may have a

problem having made such a powerful dynamic. You may need to go back and create

a flow across the canvas, if you have created a dynamic center.

Do

this methodically. Organize the painting as a drawing using the light

discreetly to create the climaxes where you want them.

Here

is a tremendous climax to nothing (D’Arista draws an image with a white area in

the upper portion). Common. Light is in areas where nothing is happening.

Chardin methodically leads the eye through. Was he lucky? Did the light

actually hit the objects? Was he faithfully recording the light?

The

photographer arranges the light. Chiaroscuro emerges – renaissance. Light and

dark are gifts to each other. By the time one gets to Rembrandt and Velasquez,

it is like a play. Light capturing and illuminating people’s personalities.

Like a person coming into a play, revealing aspects of people’s personalities.

The light comes in and reveals the painting: Caravaggio. You can come across on

the frieze with light. The light is episodic.

Rembrandt

had a chair with light coming in above it and at an angle. He would paint out

an entire figure just to accentuate a pearl.

The

Nightwatch by Rembrandt. A masterpiece in careful orchestration of the light.

(D’Arista draws a sketch of the two areas of greatest light – the head and the

praying hands). The continuity of light takes you through the painting and

climaxes.

Class

exercise: Use black instead of blue, Venetian red, yellow ochre.

Structure

a still life with light from the side only, with the light carefully

controlled. (D’Arista sets up a row of bottles near the window, with the light

coming in from one side only). To make tones, use brown underpainting using

black and cadmium red.

There

are advantages and disadvantages to this procedure. 1. It makes you terribly

aware of the importance of light. 2. Color can disguise painting problems by

confusing you with what you are doing with the light. Underpainting (primary,

preliminary investigation) - without it there tends to be diffuse importance –

nothing is emphasized. Candlelight painting (George de la Tour). They may seem

more intense and brighter than actual color paintings that may appear rather

dull and dim. Because, value shifts are so soft. Indeed, there is this about

painting outdoors. You dispose of 200 times more light than can be reflected

off of your canvas. So you are pulling some things down to make things seem

more intense. But also, if you begin dark paintings, it is hard to use strong

bright colors.

Artists

before the 19th Century considered light to be of central

importance. With open air painting it is harder to see form and reach climax

and see the hierarchical importance of things.

There

is an intimate relationship between intensity of color and the amount of light.

Each increases to a certain point and then washes out with too much light. In

Renaissance painting – things can achieve greater importance by using the light

with dark underpainting.

In

El Greco, light brings the eye around, thus unifying the figures. Painters in

Spain could use only limited palettes. Velasquez, taught by his father-in-law,

having strong lights in certain parts can either break up or unify the

painting. Constable said, “By golly, I know my chiaroscuro!”

Be

conscious of this – you don’t necessarily have to use the strong blasts of

lights. Directing light in the studio can lead to simple succinct painting.

Part of this has to do with organizing the objects, but more, how light meets

the objects. When bounce lights are omitted, you readily see the form.

Leonardo

DaVinci’s treatise on painting. Rembrandt may have used it extensively:

-Aerial perspective: one can only see

color where light hits directly.

-The lightest object is the most

visible, and the darkest object is the least visible.

-Only misted objects are devoid of

light and shade.

-Be sure there is a diminutive change in

color and sharpness as it gets farther away.

-Distance makes even sharp black less

distinct. It becomes grayer.

-Light – a broad light high (but not

from the ceiling) and not too strong renders the objects agreeably (as

Rembrandt paints)

-Lights cast from a small window aren’t

good for painting, particularly if the room is large.

-There should be a rational light

source.

-It is beautiful to paint people under

beach umbrellas and awnings.

-Do a portrait in gray weather or

towards the evening, with the sitter against a wall.

-Evening gives softness to people.

This

soft and silvery light will be very muted. Impressionists explored the intense

light. Not Renaissance painters. For outdoors painting, you may have to change

all of your rules and regulations. Nevertheless, a lot of what we are saying

are important considerations, though they have limitations.

Our

paintings don’t lend themselves readily to color. We should be conscious of how

value and light affect the way you paint. There is much to be said for never

painting this way. This way makes it easier to see how the light works.

Andrea

del Sarto. The Faultless Painter by

Robert Browning. Del Sarto was an elegant painter – lusciousness. His wife was

a terror. She appears as the Madonna in all of his painting. Leonardo did his

painting in the twilight. Silvery light lends elegance. “Love, we are in Gods

hands.” Art is not simply a matter of technique. “Less is more, Lucrezia” – the

cry of minimalists. “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp.”

The

Pantheon is a building worth looking at – a marvelous building. Raphael from

Urbino is buried there and there has always been one fresh rose on Raphael’s

tomb.

I

propose these studies to you not so you can get a mechanical answer, but to

arrive at a better understanding of what you’re doing. The silvery light occurs

because effectively, they are value studies. It is also a succinct expression

of the form. Paint thicker as you go to your full palette over the

underpainting.

Lecture

Class

exercise: First draw the silhouette and then some inner shapes with straight

lines. Also, incorporate space into the painting so that the entire square is

filled. Move to get three views. Fill new shapes in with color. It is possible

to view more by seeing it from many angles. Plato – interpreting the shadows.

Created

was a tremendous amount of space. We saw space because we walked around it.

This is not always true when you paint from one place. In 1890, one would say

“you can’t see things.” Our every instinct is to preserve the likeness.

I get you to lose likeness. Perhaps the likeness isn’t lost. Perhaps there is

more likeness now, however. Why? Look at say, Pissarro. How could they think

his painting was a ludicrous mess? Compare it to Rockwell – don’t laugh at him,

he presents fine likenesses.

The

sense of sunlight, of the way things look in that light is more accurate in

Pissarro than in Rockwell. When a student does detailed drawings of a part, he

thinks he will get a likeness. I say, “look sonny, sacrifice the details for another

kind of likeness.” You can’t always have both. Therefore, it is possible to

draw something in which you sacrifice certain characteristics to elicit others.

You see with two eyes, two views, while your painting is only one view. This is

a great problem in reproducing what you see. This may be why painters look

around the corner – binocular. Cezanne, Van Gogh, Delacroix – “He shows you the

front, but you can see the back.”

Class

exercise, cont’d: Next – do a straight forward painting, then move 2 steps to

the side and continue painting. Most of you after painting 4 or 5 years paint

with one eye squinting. Explain the space by changing perspectives. In changing

things you explain more than if you duplicate. Painting as an interpretation –

not a duplication. Decide what is expedient for you in deciding what will give

the space. In Cezanne, the figure seems close, but the open book’s perspective

shoves it back. This permits us to understand space. Paint as you normally

paint – react radically to the incidents of space. Feeling a cutting in and out

of space – not searching for the objects.

For

the head, find the side and the top, even if you don’t see it, of the head. Now

it is possible to find the complexities. You diminish space by flattening the

objects. Emphasize space by getting planes, even the ones you don’t see from

one viewpoint to move through the space, even if you have to distort. Too many

young painters find they can understand space by cylinders, causing

mechanicality and syntheticness.

Everything

you see is light. Consider: The problem is almost impossible if you consider

painting to be just smearing around color. You can’t duplicate what you see,

only parallel the experiences. Done carefully, a good illusion is created. The

commonest error by the early student painting in dim light is to try to make it

whiter. Whiteness depends not on how white you can get, but how dark you get

around it. Warm and cool relationships will influence your perception of the

painting as being intense.

With

the red, yellow, and blue underpainting, it is very bright. Why? Why is it

throwing off more light than is being thrown on it. Why? Well, begin at the

beginning. This white light is composed of all colors of the spectrum. White

light breaks up in the prism. Thus, Newton was able to demonstrate that: Red on

red glows. Green absorbs all light of the spectrum except green. That it

reflects back. Thus objects look green. Pigments function by destroying light.

Blue absorbs red and yellow and reflects green and a lot of blues.

There

are ways of producing color other than destroying light. There is color by

destruction and addition. All pigments mixed together – you get gray. It is not

based on reflecting any part of the spectrum. Optical mixing can occur in the

eye. Leaves from afar – leaves appear orange. From close up – red and yellow.

Seurat does this with separate dots of color. We see color as a process of

light deduction. The mixture of light through the addition method gives

brighter painting – gives more light.

A

Rembrandt compared to a Monet: more light is in the surface of the Monet, even

though the Rembrandt has an inner glow.

Sir

Thomas Young: If color is as Isaac Newton says it is, then are we presumed to

have a thousand eyes, one for each color? He thought not. The night has a

thousand eyes, the day but one. He hypothesized the 3-eye theory. Blue, green,

red. If all three of these eyes are stimulated at once, you see white.

Afterimages:

Just as the tongue is sensitive to new food, in the presence of no stimulation,

just blue, then the red and green eyes will open up. Then, suddenly presented

with white light, the eye will see no blue at all, thus explaining complements.

The blue eye is fatigued, and thus you see its complement. This is optical

fatigue. Thus, to make violet appear more violet, put yellow around it – to

make the eye tired so it can see more of the violet.

Thus,

we understand primary colors. Really, no colors are more important than any

others. There are 6 billion of them. It is primary because of the way our eyes

work. Not because of the colors’ physical properties.

The

primacy of yellow dispute: If you can do it with blue, green, and red, then you

have three primacies. Thus, R, G, B are true primaries. C Y M (cyan, yellow,

magenta) are pigment primaries.

Flesh

tones of Madonnas are underpainted in green. Green brings out red. More

important is the color of the light. 19th century – open air. North

light is cool and bluish, giving warm shadows. Green light makes the white wall

around it sink. The red light gives a bluish cast on a white wall.

Red

and green light gives yellow. This is all additive. And blue is seen in the

deepest shadows. Thus, with two colors, the entire spectrum is seen.

Always,

the color of the shadow tells about the light. Warm brown shadows indicate

indoor painting from North light. Blue magenta – outdoors.

So,

the three colors create the illusion of sunlight, producing cool middle values.

I

paint from a light source with two different lights in order to study the shadows

better. Like Sherlock Holmes, examine certain details – clues to get the whole.

Lecture

Pure

schematized composition – much more instructive. “Alarm clock school of

composition.” With our methods, one becomes aware of the planes and tensions

that occur. The loose, casual idea of treatment of these compositional ideas

can be used with intuition to bring balance to the painting, like clockwork. So

you have many tensions, hence my cute little metaphor “clockworks.”

This

kind of value is implicit, but it is too narrow. Bleaching out value and

softening the planes.

Homework:

Begin a painting. Not from life. Incorporate elements that are not together.

Imaginative, the making of images. Look at me – now – put foxes ears on my

head. You have simply moved one image around. For another painting – paint it

in one room with the objects in another room.

On another, do separate objects and put them together. Like Jack Boul at

the canal taking sketches and then bringing them back to his studio and putting

them together. This forces you to memorize before you paint. For the next two

weeks, we will focus on this. Don’t paint directly from life. You can use

sketches or photographs of people.

This

is the introduction to the idea of putting a painting together without the

objects being there. Raphael did this. You can put a photo of a person in a

landscape you have a sketch of. Eventually we will do a triptych.

In

Renaissance painting, there was no painting from life. But it was not

completely a figment of anyone’s imagination. This has an ancient and honorable

history. James ____ suggested (and Turner used) inkblots

like Rorschach and

smeared them together for a landscape. I felt comfortable doing this

after 26 years of painting. I could remember what things look like and where

they were. Positioning between things is what one has to remember. The best

possible way to do this is to paint from life for years. Skip Paul [a student

from a previous year] took a couple of figures from Piero and Raphael and put

them together.

The

painting must be put together. This is very hard because our training has been

very impressionistic. Some people get bizarre surrealistic paintings, some just

get bored. One must find out. One idea may not be good. Don’t stick to one

thing. Ensor. Use three planes, inner squares, the golden section, the whole

bit.

Composition

isn’t something which you impose on a painting to make it look attractive. It

has to do with the structure of the expressive statement. It functions to

declare what the artist wishes to express or say by making what he says

clearer. The frieze helps you understand painting better. So does the grid.

Thus, there is not composition and then expression, but the two are intimately

related.

Poussin

said that there are various modes of expression, Doric was severe, harsh, etc.

He was guided by the intervals that met the expressive needs of the painting.

Intervals – you can recognize division of time that has expressive intent so

that the divisions are very important to the painting.

A

cognitive function interval or architectural placement of the space. She

was dressed in pure white with a blue cap on her head: distance, remoteness,

pureness. Hot colors we associate with life. And we use colors in this way. We

use colors operatically, and we look at the painting in terms of rhythms,

color, space and we see the associations that come out of the artists. Colors

chosen are not prosaic colors. They convey messages. Anything too specific

closes off the train of associations. Obvious symbolism that is stated is

always narrow and limited. Italian Renaissance painting sought acceptance by

masquerading as realism. In Caravaggio's Conversion

of St. Paul it is not important to have sharply delineated iconography.

In

Chinese art the principle of division is the same, but more rhythmic. Artists

influenced by the Japanese have more ambiguous space and simple continuous

movement, not rational space. It is woeful that we don’t identify objects in

place or time. A picture doesn’t have to be symmetrical to have balance, and

being symmetrical is far from the ideal balance.

Composition

scheme: put something very large in the foreground and run a circle around it.

Triptychs

We

enter a part of painting that is perhaps a region of the unknown. Japanese screens

refute what I say about triptychs. The question of time intervals is always the

rationale for triptychs and diptychs. The question of time in a painting is at

the heart of our discussion today and is very important to the history of art.

In fact, you may be moved by subject matter in terms of their sequencing. At

the very core of your existence, the two address to you as neither could

separately. There is a simple statement made here. One represents the

crucifixion and one is the last judgment. Vindication at every level, the first

becomes the last. This is a profound human reaction we all feel. Most

universal. So there is a sequence in time and space that allows the art to

achieve this multiplicity. The last judgment hasn’t happened yet. So it is prophesized.

How would they be attired today? Perhaps in space suits would be more suitable.

In this Caravaggio, they are in costume. If you pin it down to a particular

time with period clothing, it loses its universality and mysticism. Like

Kandinsky – “one must destroy space to transcend.” Now, also time.

Students

reacted violently to painting a TV set. They could not conceivably understand

how to relate the object to a still life. The heart of the symbolism is what

happened and what will happen in the future, but not with right now.

Another

triptych: four disparate events unified with the same landscape. Interesting.

Why? Why do we ignore the unified landscape – we are so familiar with it. It

represents the Earth and the universe. He has contradicted time and space and

made it ambiguous to become spiritual (not to destroy it). This makes it more

provocative than a rational sequence of time. Mary Worth [comic strip] –

rational when intensions are serious, when you can conceive of a sequence that

is rational in time. You construe it in literal terms. Getting rid of time

gives it its transcendence. We’ve grown use to this device. Gives a jump in

time.

This

is very important in terms of this art not being prosaic or trivial. Now we see

why the oriental screen is the exception to the triptych as I have explained

it.

Philip

Guston (Phillips Gallery) you see the oblique and incomprehensible. His

painting is in the grand tradition. Symbolism is involved in the suspension of

time, and the assertion of rational space is important in allowing our mind to

dwell on the incomprehensible. It affects you at your most profound level of

existence, and the logical militates to that end. Thus, we can discuss the

concept of guilt aspiration (Judeo tradition). Guilt cannot exist out of the

context of aspiration. The notion of guilt, repentance, forgiveness, and

temptation – you are at the heart of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Another

Guston– called Departure. No space or time, but terribly cruel subject matter

done in a rather comic strip way, which makes it possible to accept. Otherwise,

it would be too hideous to confront in the psyche. The catharsis – involvement

of seeing dreadful things on stage in Macbeth – the chorus in Greek plays

functions in the same way, putting distance between you and the hideous,

gruesome truth. When someone says in an argument “say what you mean,” well who

in the world knows what they mean?

Paint

the likeness so that you are certain it is exactly as you see it. The

psychological truths seem to invite an aimless inventiveness, which compels you

to paint something you know is true. I don’t know what it means, I simply vouch

for its fundamental veracity.

Iconography

in time is always the most difficult problem in art. An element of the

illogical may be an absolute necessity here. Deny time to achieve. The

diptych/triptych does involve time more than other painting.

Format and

Subject Matter in Triptychs

These

matters are difficult to talk about, but can and must have considerable

meaning.

In

the book triptych – the sequence is related. Unity is missing in the student’s

work. The reason may not be to connect the three, but to have a reason for the

shift. Visual specificity is lacking in the small one. The large one is quite

pressing and urgent. The two are connected too rapidly. You can aimlessly

generate a painting in a square, and that should be avoided.

If

she [a student in the class] began to measure space with our composition

devices, the space would measure more. Her triptych reflects the fact that she

doesn’t take each individual painting seriously. Each painting of the triptych

should function individually as equally important. We are not all inclined to

this kind of painting. I do it because it presents options.

There

is nothing in my painting that lends it to this public viewing. It is too hot,

too intimate. It can’t be tolerated. There are only certain things we can share

together if there are more than one hundred of us. A very formal architectural

design can be important in pushing things away from you. In keeping aesthetic

distance. This formality lends itself to public treatment. Some paintings would

function in large theater halls, where a Vuillard would not.

Class

exercise: Do three triptychs rapidly in half an hour:

- The

judgment of Paris

- The

destruction of DC

- The

murder of your mother

Some

ideas can only occur in the process of painting. I was taught to keep a

sketchbook to cultivate the images. Nameless place, not the destruction of

space, but “never mind what the space is – see the event.” The history of

painting from life is very short. It starts in the 19th century.

Most painting is not from life. There is something to be said for examining

that phylogenetic pattern and following it for a bit. Still life and figure

painting should have the same urgency. Painting from life, you think of your

treatment as accidental and you put out effort. But in these paintings, the

dynamics just flow from the brush. Pursue this idea at home, and bring your

work in next Tuesday.

It

is best to work from life for a very long time before working from memory and

imagination. Imagination is the ability

to make images. There is an attitude towards painting that says not to

concentrate on value, space, or detail, but to put down simply the most beautiful

colors you can. Put down the color that flips you the most. Color takes on a

symbolic quality. In any kind of painting you must have this component.

Morandi

– deep emotional effort and narrative is the intention. Still life is important

in the intention of the painting. The French meaning for still life is ‘dead

nature.’ Morandi had heightened detachment.

The

purely descriptive can be at war with the mythic or symbolic. You must make

decisions by yourself on how to combine the two.

One

criticism of painting: architecture of a certain period in a painting can date

something and make it of a time rather than being mythical.

Somehow,

one has a better grasp of how much detail to put in the paintings from memory.

In

doing a figure grouping, look in terms of contrapposto

and tensions of poses. Go to Daumier. Look for a pyramid structure – a 3-D

pyramid. The spacings between figures are very important.

Do

several color sketches. The only time you are really thinking is when you put

down your idea, as in quick sketches.

Lecture

The

severest form of simplification is the use of angles. The right angle has

maximum opposition and is simplest to measure and understand. You might agree

that you can strengthen a painting by putting in this reduction to angles. Use

30 degrees or 40 degrees or not exact measuring, but use angles. You are

simplifying the painting and strengthening it. The painting is also more

designed this way. But we lose something of the identity. Why?

This

procedure is true with verbal information also. As we move to greater

specificity, we arrive at identity. Is there anything precisely the size of the

gold bar? No! There are no two things in the whole world that are precisely the

same size. So a person can never step into the same room twice. In an effort to

get a larger group you become less precise and specific. “How many here are

short?” To, “how many here are human?” We draw an arm precisely, we think, but

then we look to see there is no identity.

You

suppress trivial differences to arrive at a broader category. This is very

important to the history of thought and idea (math depends on it). We can

reduce the human figure to certain geometric shapes (Cezanne). In doing so, we

will suppress part of the likeness. This – the beginning painting student

resents most. But by doing it, one is capable of encompassing grand things. The

entire world and matter: Energy = MC squared. Suppress identity and differences

in order to do it. The beginning student speaks with too much particularity.

You

could spend three hours describing a car because it is unique, but its

uniqueness is trivial. It is a blue Volare – a dirty rotten car. If I carry on

about the color for four or five hours, I might drive you out of the room. The

ineffable characteristics that will make the color work. Ann McGurk [a student

in this class] is three-quarters the size of the wall. We don’t need to measure

her against a gold bar. To a Japanese autoworker, we all look the same.

Class

exercise: Use red, blue, yellow, white,

and black, 90-degree angles, and all distances related to each other. Suppress

trivial information and characteristics for more meaningful ones. Get rid of

the nuance colors. Lines are either vertical or they recline.

What

things are is irrelevant. We object to the bottle and see it as an eyesore. It

was too particular. This should tell you about relationships and why we are so

sensitive to them. Accidents are boring. The paintings approach the grid-like

mechanism – a theosophical miracle. As you begin to illuminate detail, there

are more geometric shapes toward Euclidean perfection, because you have

eliminated irregularities with distance. The grid-like pattern orders reality

for you. Math is the purest expression of this reductiveness. It transcends

particularity and reality to transcendental truth. If you can arrive at a pure

relationship, it may be the most satisfying and universal relationship you can

make. You approach a Mondrianish expression of relationship.

You

don’t mind the particularity of the triptychs. There is a context for

statement. You may not violate it easily. There is always a hidden rule to

determine what you can and cannot say. We are approaching a visual mathematics

form of painting. Relationship without identity. It begins to answer to the same

rules as mathematics. If I were to say to you about math, that all of its rules

were subordinate to the rule of equivalence, so it is with that kind of

painting.

Mondrian’s

essay on Neoplasticism: I consider Mondrian right about everything he says, except

his fundamental premise and his conclusion. Man adheres only to what is

universal. With the single primordial relation, the right angle, tension is

directed toward the universal. Particularity is an affront to higher

consciousness. Are the paintings we have done elevated, urgent, universal, and

more compelling? You can reduce Rembrandt to pure artistic statement. Primitive

art lacks particularity (pyramids, Egyptian figures, etc.). These are not more

satisfying than Rembrandt. The notion that one can reduce reality to polarity

seems ridiculous. To reduce life to pure relationship fails at the artistic and

verbal level. Most of the world believes something very close to this.

I

believe in measure and statement as being not necessarily reduced to pure reduction.

But they don’t get better as they get more realistic either. After all, a great

many people believe that all of reality is moving to a higher form of

disembodied truth.

_____________